Free Features

Free revision policy

$10Free bibliography & reference

$8Free title page

$8Free formatting

$8The Video Report!

As you watch the video link at the end of this assignment of Mitsuko Uchida performing W.A. Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor for piano and orchestra, K. 466, consider how the work would have been performed in Mozart’s own time — with the composer himself at the piano. We have learned that music in the Baroque era was conducted from the harpsichord. Music in the Classical period was conducted by the concertmaster (first violin, first chair), although with the tendency of older traditions not to be given up entirely in the face of new once, Mozart very likely conducted this work from the keyboard, just as Ms. Uchida does in this video.

As you prepare this assignment, imagine yourself in 1785 Vienna seated in the audience next to Wolfgang’s father Leopold, who had come from Salzburg to visit his son. Below is a short excerpt from Neal Zaslaw’s book “The Compleat Mozart” on the concerto and the performance through a father’s eyes (although Leopold was not always so kind). Sections in square brackets [ ] are my own.

Neal Zaslaw, “The Compleat Mozart” excerpt

February 10, 1785.

On this day “…Leopold Mozart arrived [in Vienna] to spend a few weeks with his son and daughter-in-law. [Mozart had married Costanza Weber by this time.] He reported to his daughter Nannerl [who was back home in Salzburg]:

We arrived at one o’clock. . . . The copyist was still copying when we arrived [consider that the parts for the orchestra are still being copied only a few hours before the performance. Performers played from hand-copied scores more often than not during the Classical era. The luxury of published parts is not enjoyed until much later], and your brother did not even have time to play through the Rondo, as he had to supervise the copying. . . . On the same evening we drove to his first subscription concert [of six], at which a great many members of the aristocracy were present. [This comments tells us that Mozart must have been quite popular to draw such an illustrious crowd.] Each person pays a souverain d’or or three ducats [unit of money at the time] for these Lenten concerts. Your brother is giving them at the Mehlgrube [the name of the concert hall] and only pays half a souverain d’or each time for the hall. (There were more than 150 subscribers.) [Leopold’s statements about profit betray his concern about finances, one that extended through much of his life.] The concert was magnificent and the orchestra played splendidly. In addition to the symphonies, a female singer from the Italian theater sang two arias. Then we had (the) new and very fine concerto . . . . [K. 466] [These last comments remind us that a concert at this time in history was quite long. They would frequently begin with a movement from a symphony, move on to both vocal and instrumental chamber music selections and finally end with another large-scale work, in this case a piano concerto. Three hours or more was not unusual for the length of a concert.]

The orchestra musicians must have been outstanding and well acquainted with Mozart’s idiom to have satisfied his sophisticated father and the Viennese audience in a sightread performance of this subtle, difficult work [Recall Leopold’s comment that Mozart didn’t have time to run through the last movement (rondo).] Perhaps because of its wide range of affect, brooding chromaticism, and stormy outbursts, K. 466 – one of only two concertos Mozart composed in minor keys – was a favorite in the nineteenth century, even though its final seventy-five measures in D major represent a clear instance of an eighteenth-century lieto fine (happy ending), which nineteenth-century musicians found so hard to accept.

[The nineteenth-century audience would have expected a minor key ending in keeping with the general mood of the movement.] The young Beethoven had K. 466 in his repertory and wrote cadenzas for it, as did Mozart’s pianist-composer son, Franz Xaver Wolfgang. Mozart, however, did not leave any cadenzas himself. [This is not surprising in that Mozart wrote most of his piano concertos for his own public performance, so there was no need to write out a cadenza. He would have treated it as a Baroque performer would – an opportunity for improvisation. Many works, not only Mozart’s lacked written-out cadenzas. This was, in fact, the only designated opportunity for a performer to improvise, something that had been an essential part of Baroque performance throughout a work.]1

1Neal Zaslaw, ed. The Compleat Mozart (New York: W.W. Norton

Essay Writing Service Features

Our Experience

No matter how complex your assignment is, we can find the right professional for your specific task. Tutoracer is an essay writing company that hires only the smartest minds to help you with your projects. Our expertise allows us to provide students with high-quality academic writing, editing & proofreading services.

Free Features

Free revision policy

$10Free bibliography & reference

$8Free title page

$8Free formatting

$8How Our Essay Writing Service Works

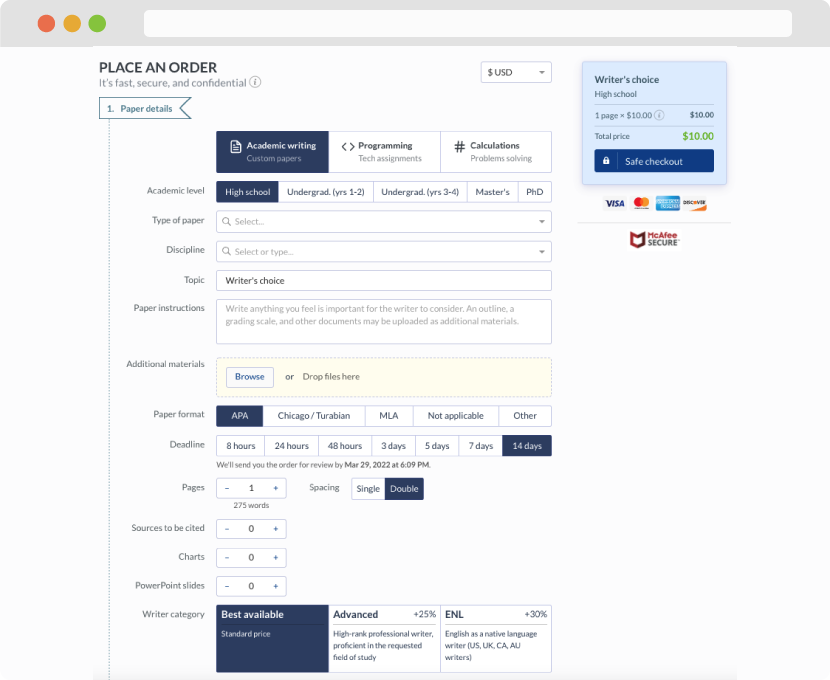

First, you will need to complete an order form. It's not difficult but, in case there is anything you find not to be clear, you may always call us so that we can guide you through it. On the order form, you will need to include some basic information concerning your order: subject, topic, number of pages, etc. We also encourage our clients to upload any relevant information or sources that will help.

Complete the order form

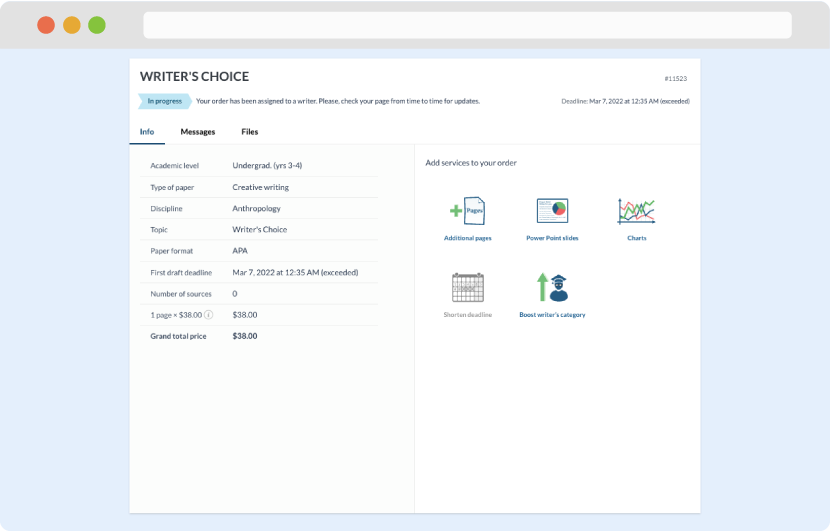

Once we have all the information and instructions that we need, we select the most suitable writer for your assignment. While everything seems to be clear, the writer, who has complete knowledge of the subject, may need clarification from you. It is at that point that you would receive a call or email from us.

Writer’s assignment

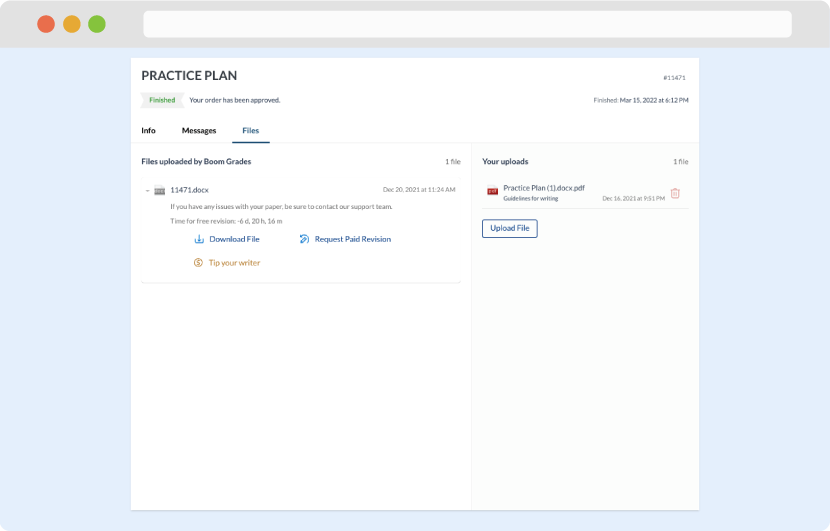

As soon as the writer has finished, it will be delivered both to the website and to your email address so that you will not miss it. If your deadline is close at hand, we will place a call to you to make sure that you receive the paper on time.

Completing the order and download